The Jesuit poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, was born July 28, 1884. I spent time in prayer, the practice of Lectio Divina, with his poem “God’s Grandeur.”

God’s Grandeur, Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889)

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs–

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Often, we do not pause long enough to appreciate the grandeur, “like shining from shook foil”, that exists in our ordinary day, whether in parenting, work, recreation, prayer, or service. We become task-oriented, rather than living the process; focused on results, rather than what we can learn and how we can grow from an experience.

We have been trained by our culture, but this pandemic has stopped us in our tracks— “generations have trod, have trod, have trod.” Our economy, “seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil” is, seemingly, our measure of worth. Our livelihoods, the means from which we carve out our place in the world, provide service to others and money for our pocketbooks. Unquestionably, we need income to provide food, water, shelter, health care, education, and, hopefully, enjoyment for ourselves and our family.

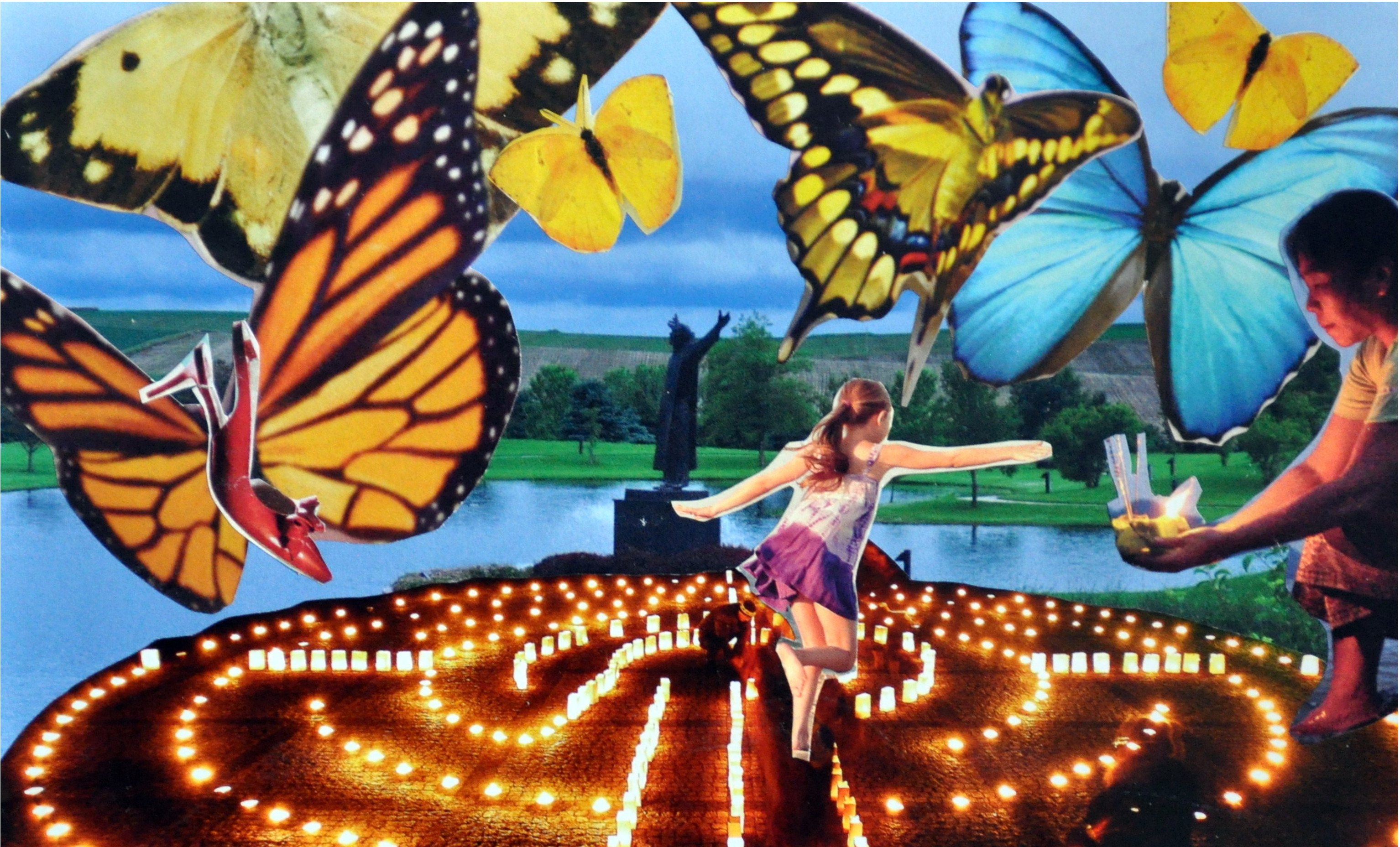

I do not think Manley suggests we spend our time living a life of carefree leisure, enjoying the birds and the butterflies, and avoiding all hard work. But perhaps, he is asking—what is it all for? What do we toil for? What must we remember?

Humility, a foundational value of Benedictine spirituality, requires us to admit that we do not know it all, despite our secret desires or belief. In humility, we must accept our vulnerabilities, acknowledge our weaknesses, and desire our will to align with God’s. We accept responsibility for our community, knowing it is not just about us, and recognize that our spiritual conversion is a lifelong journey. We welcome that each new day or experience brings fresh insights and deeper levels of understanding—in relationship with others, self, creation/nature, and God.

I am grateful for the unfolding of time—to experience, to learn and grow, to become more of who I was created to be. There is a sense of surprise and discovery hearing an idea or perspective I had not considered when reading a good book or attending a spiritual retreat, or trying a new strategy in the classroom that helps me connect with students, or in the enjoyment of watching my adult child establish her career, or seeing the changes in nature from season to season.

“And for all this, nature is never spent; There lives the dearest freshness deep down things.”

I stand in awe of our Creator and of all things created and becoming, for the world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It takes a slowing-down to appreciate the sacredness of the ordinary. In the snippets of headlines and social media posts, we have become accustomed to the fast-food delivery approach to news and the over-abundance of information. But to fully appreciate the beauty of words, savoring good literature or commentary requires a commitment to read, reflect and ponder, with a highlighter in hand, rather than falling down the rabbit hole of the Internet. (it is impossible to read the whole internet in one night, despite my repeated attempts.)

To stand in awe we must relish, cherish, behold.

To behold is to regard, gaze upon, view; watch; discern.

To relish is to have a hearty enjoyment or appreciation.

To cherish is to treat with affection and tenderness, to hold dear, to treasure.

This takes time and intention—and yes, humility. The circumstances of the pandemic challenge my need for control and certainty (this, too, is an illusion, I realize.) At times I am overcome with anxiety, anger, exhaustion, and worry about what is to come, but it is in creation, the greatness of nature that I can return to centeredness, to peace, even if more that moment. “Like the ooze of oil crushed,” we find richness, a treasure, by going within and celebrating the gift that nature brings.

It requires intention and determination to see in this new way. It can be challenging in ordinary times, but the pandemic stressors are a sharp reminder of the value of humility, learning, becoming, beholding, relishing, cherishing.

We can try this idea when considering the difference between eating and dining. Eating is grabbing the all-too available cheeseburger and fries at a fast-food restaurant, eating on the run, while rushing to the next appointment or the mindless eating of just one more chip from the bag. Dining is relishing in the “sacramentality” of the food. “Sacramentality”, according to Fr. Larry Gillick, SJ, is seeing beyond; looking not just at the accidentals of, say, an apple—the color, the size, the variety—but looking at the sacred aspect of the apple. The sacramentality of the apple includes the seed from which the tree grows, eventually budding and blossoming; children playing and families picnicking underneath the tree; and, finally, the tree bearing fruit to satisfy taste and hunger.

An apple is not created in an instant; it is created over time. An apple becomes. Starting as one thing, it becomes something new, albeit, at its core (no pun intended), it is an apple. As legend holds, Martin Luther claimed, “If I knew I were going to die tomorrow, I’d plant an apple tree today.” Perhaps a statement of hope, an acknowledgment of the sacredness ordinary holds, or an assurance that we must consider the future and our responsibilities to others. The apple is much more than what we see.

Our lives are much more than our toil. While we can literally feel “spent” from worry and work, “nature is never spent.” Staying connected with the ground of our being, our feet standing squarely in creation, is a reminder that we are not the Creator, but we are not separate either. We are much more than our toil. We are becoming.

We have much to learn about ourselves and each other in this time of pandemic. It is so terribly humbling. But again, what is it all for? What do we toil for? What must we remember?

I pray for— and believe that— the morning awaits this dark night, that one day our toil and trod will be remembered as “the last lights off the black West”, that we will have become new as “morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs”—that as nature is continually renewed, we are as well.

We toil in and for our becoming. We will become new creations, by the grace of “the Holy Ghost over the bent world” brooding over us as a mother hen would her chicks. “This final image is one of God guarding the potential of the world and containing within Himself the power and promise of rebirth. With the final exclamation, (“ah! bright wings”) Hopkins suggests both an awed intuition of the beauty of God’s grace, and the joyful suddenness of a hatchling bird emerging out of God’s loving incubation.” (Spark Notes Summary) We are becoming.

Practice Lectio Divina with Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem, God’s Grandeur. You can listen to it here.

Read a summary reflection of God’s Grandeur here.

Read “The Birds Are My Prayer,” a reflection on my favorite pandemic pastime here.

![Apple Pictures [HD] | Download Free Images on Unsplash](https://images.unsplash.com/photo-1567306226416-28f0efdc88ce?ixlib=rb-1.2.1&w=1000&q=80)

July 28, 2020 at 2:27 pm

I’m also a Hopkins fan, and I enjoyed this post.

LikeLike